INSIGHT - A Systems Approach to Entrepreneurial Universities

This post is based on research published in our paper “Not Seeing the Forest for the Trees? A Systems Approach to the Entrepreneurial University” (Wurth et al., 2024).

Introduction: Missing the Forest for the Trees

In recent years, universities have been increasingly expected to contribute to economic development beyond their traditional missions of teaching and research. This has given rise to what we call the “entrepreneurial university” – institutions that engage in a wide range of activities from technology licensing and spin-offs to collaborative research and consulting with industry partners.

As academics, we’ve studied these entrepreneurial activities extensively. Yet something has been missing in our approach. We’ve largely focused on individual activities, specific institutions, or isolated case studies – effectively examining the trees while missing the forest. In our recent paper “Not Seeing the Forest for the Trees? A Systems Approach to the Entrepreneurial University,” my colleagues Niall MacKenzie, Susan Howick, and I argue that we need a more holistic understanding of entrepreneurial universities that captures their inherent complexity and interconnectedness.

The Problem with Current Research

The current academic literature suffers from three key limitations:

- Isolated focus: Studies typically examine single activities (like licensing or spin-offs) without considering how they interact with other activities within the university.

- De-contextualization: Research often fails to consider the broader ecosystem in which universities operate, treating them as isolated entities rather than parts of a larger system.

- Static perspective: Most studies provide snapshot views rather than examining the dynamic evolution of entrepreneurial universities over time.

The result is a fragmented understanding – what we refer to as “unit theories” of constituent parts without considering the wider feedback effects and implications. We’re looking at individual trees but missing how they form a complex, interconnected forest.

A Systems Thinking Approach

To address these limitations, we’ve developed what we call a “programmatic theory” of entrepreneurial universities using a systems thinking approach. Rather than focusing on isolated components, we’re examining how different activities, capabilities, and contextual factors interact and influence each other over time.

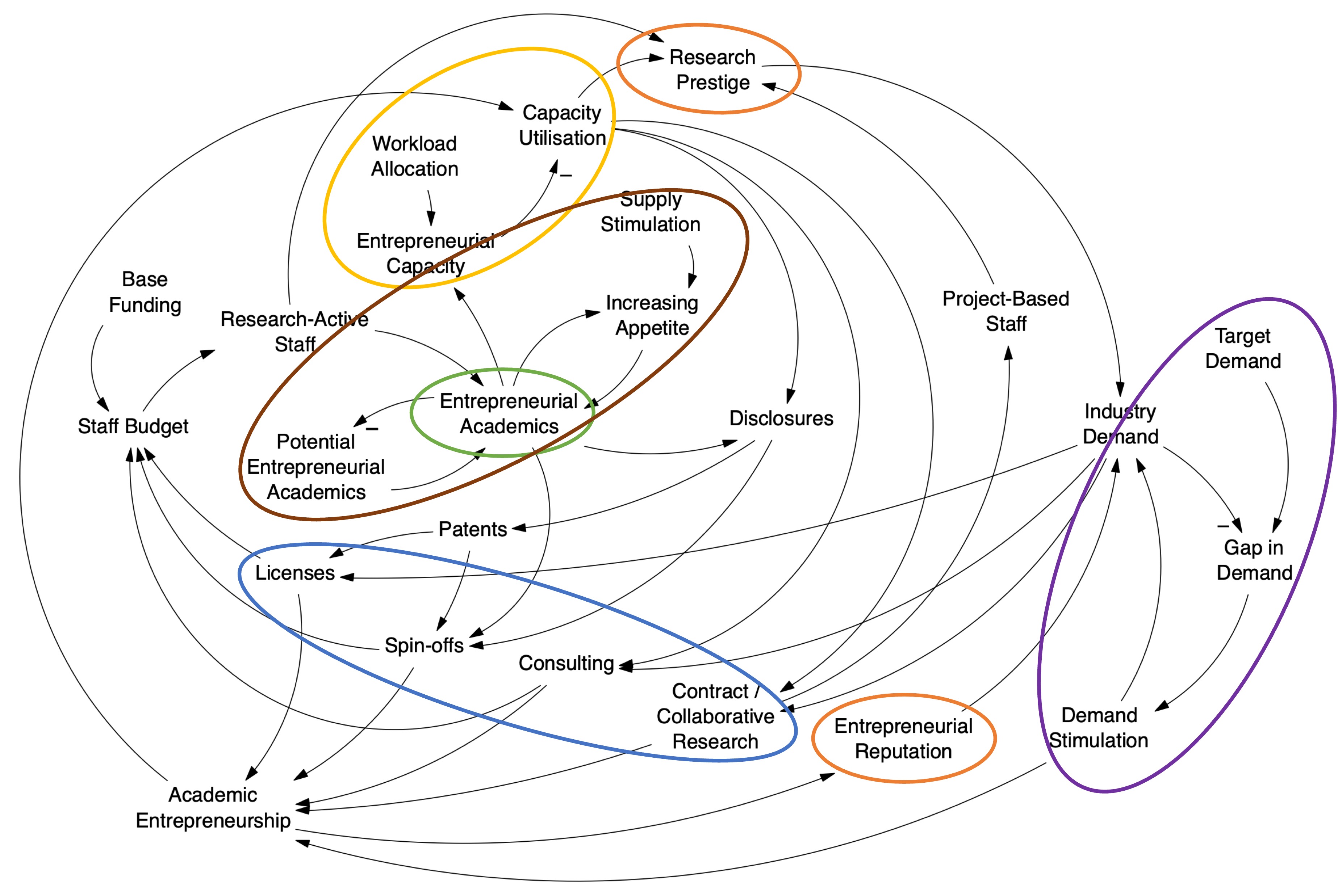

Our research combines qualitative interviews with technology transfer office directors and staff from seven Scottish universities with quantitative data from various national surveys on university-industry interactions. We’ve synthesized these insights using causal loop diagrams (CLDs) – a tool from system dynamics that visualizes the interconnections and feedback loops within complex systems.

The Entrepreneurial University as a System of Feedback Loops

So what does this systems perspective reveal? Let me walk you through some key insights from our model.

Research and Commercialization Dynamics

At the heart of our model is the relationship between research activities and commercialization. Universities conduct research, which can lead to discoveries and inventions. These may be disclosed to technology transfer offices, potentially leading to patents, licenses, and spin-off companies. The income generated from these activities is often reinvested into further research, creating a reinforcing loop.

However, this is just the beginning. Our research shows that commercialization processes are far more complex than the linear models traditionally depicted in the literature. For instance, we found that only about a third of university spin-offs are based on disclosed and patented inventions. Many are created directly by academics without going through formal technology transfer mechanisms.

Entrepreneurial Academics as Key Agents

Our interviews revealed that most entrepreneurial activities involve a relatively small number of “entrepreneurial academics” – faculty members who actively seek opportunities to engage with industry partners. These individuals are crucial bridges between the university and external organizations.

The total number of these entrepreneurial academics and their workload allocation define the “entrepreneurial capacity” of each university. When the amount of external engagement exceeds this capacity, universities face potential detrimental effects on their other missions. This creates balancing loops that limit growth unless universities can increase their entrepreneurial capacity. Reputation and Demand Dynamics

Universities don’t operate in isolation – they’re embedded in ecosystems with various stakeholders, including industry partners. Our model shows how research prestige and entrepreneurial reputation influence industry demand for university collaboration.

Companies typically follow a two-step decision process: first identifying a need for external input, then choosing their preferred academic partner. Research excellence attracts industry attention, but previous successful collaborations build entrepreneurial reputation, creating reinforcing loops that can accelerate future engagement.

Supply and Demand Stimulation

Universities can grow their entrepreneurial activities through two main levers: internal supply stimulation and external demand stimulation.

Internal stimulation involves increasing the number of entrepreneurial academics through incentives, skill development, and strategic hiring. External stimulation includes proactively engaging with industry, demonstrating expertise, and building relationships.

Importantly, our research shows that universities must balance both approaches. Focusing on one at the expense of the other merely shifts the bottleneck rather than enabling sustainable growth.

Practical Implications: Lessons for Universities and Policymakers

What does this systems perspective mean for university leaders and policymakers? Here are some key takeaways:

For University Leaders:

- Recognize trade-offs: Increasing entrepreneurial activities without a balanced approach risks undermining other university missions. Our model helps visualize these potential trade-offs.

- Develop dynamic capabilities: Universities need capabilities that allow them to sense changes in the environment and adapt accordingly. These go beyond static resources to include organizational learning and flexibility.

- Cultivate partnerships, not just transactions: Long-term relationships with industry partners yield more value than one-off interactions. Universities should transition from a contractor mindset (offering “knowledge on a market basis”) to a partnership approach.

- Balance supply and demand stimulation: Growing entrepreneurial activities requires both increasing internal capacity and generating external demand. Focusing on just one creates bottlenecks.

For Policymakers:

- Look beyond commercialization: Policy support should extend beyond narrow metrics like patents and licenses to encompass the broader range of entrepreneurial activities.

- Support capacity building: Effective policies must help universities develop the capabilities to manage complex entrepreneurial activities while maintaining excellence in teaching and research.

- Treat university engagement as a “commons”: When universities actively engage with external organizations, they benefit the entire higher education sector by demonstrating the value of academic collaboration.

- Consider systemic impacts: Our model helps policymakers anticipate how interventions might affect different parts of the system, potentially revealing unintended consequences.

The Value of Systems Thinking in Practice

Let me illustrate the practical value of this approach with an example from our research. One university we studied wanted to increase its industry engagement. Initial discussions focused on marketing and promotion strategies to attract more companies. However, our systems analysis revealed that entrepreneurial academics were already at full capacity.

Without addressing this internal constraint, additional marketing would have created frustration as academics couldn’t take on more projects. By understanding the system as a whole, the university could develop a more balanced approach – gradually increasing academic capacity while strategically growing external demand.

This example highlights why seeing both the forest and the trees matters. Understanding individual components (trees) is necessary but insufficient. We must also grasp how they interact within the broader system (forest).

Future Research Directions

Our work opens several promising avenues for future research:

- Methodological innovation: We need approaches that can capture feedback loops and interdependencies, such as system dynamics modeling and network analysis.

- Data integration: Rather than creating new datasets for each study, researchers should combine existing data to gain more comprehensive insights.

- Contextual variations: How do entrepreneurial university dynamics differ across geographic and institutional contexts?

- Teaching-entrepreneurship connections: Future research should explore how teaching contributes to entrepreneurial universities, particularly in developing skills and entrepreneurial mindsets among graduates.

Conclusion: Embracing Complexity

In conclusion, understanding entrepreneurial universities requires embracing complexity rather than avoiding it. Our systems approach offers a more holistic perspective that reconciles existing “unit theories” into a coherent programmatic theory.

For university leaders, this perspective enables better strategic decision-making by helping diagnose capabilities and identify leverage points for improvement. For policymakers, it provides a framework for developing more effective support mechanisms that account for interdependencies and potential unintended consequences.

By seeing both the forest and the trees, we can unlock the full potential of entrepreneurial universities to contribute to economic development and address societal challenges.